When Elections Can Be Merely Symbolic

- Mike Kosor

- Sep 24, 2025

- 9 min read

Nevada’s lawmakers, in adopting our current HOA laws, intended to strike a balance — giving developers just enough authority over homeowner communities to finish its project, while ensuring that control would pass- sooner than later- to the owners. But, as too often happens, developers and their lawyers have found loopholes to sidestep that balance.

One HOA in southwest Las Vegas has been under the developer’s control for over 26 years, contracts the management of operations with a company wholly owned by the developer, and all is in plain sight. It is unlikely to be operating illegally and may be an outlier — but it is not alone. And keep in mind this HOA has yet to use any of the loopholes identified below to retain its control. Read more here.

This blog identifies two of the most significant weaknesses in Nevada law. Each was originally purposeful, but each has opened the door to abuse.

Unless regulators and the Legislature act, Nevada will never achieve the balance it promised homeowners.

First, Two Misconceptions

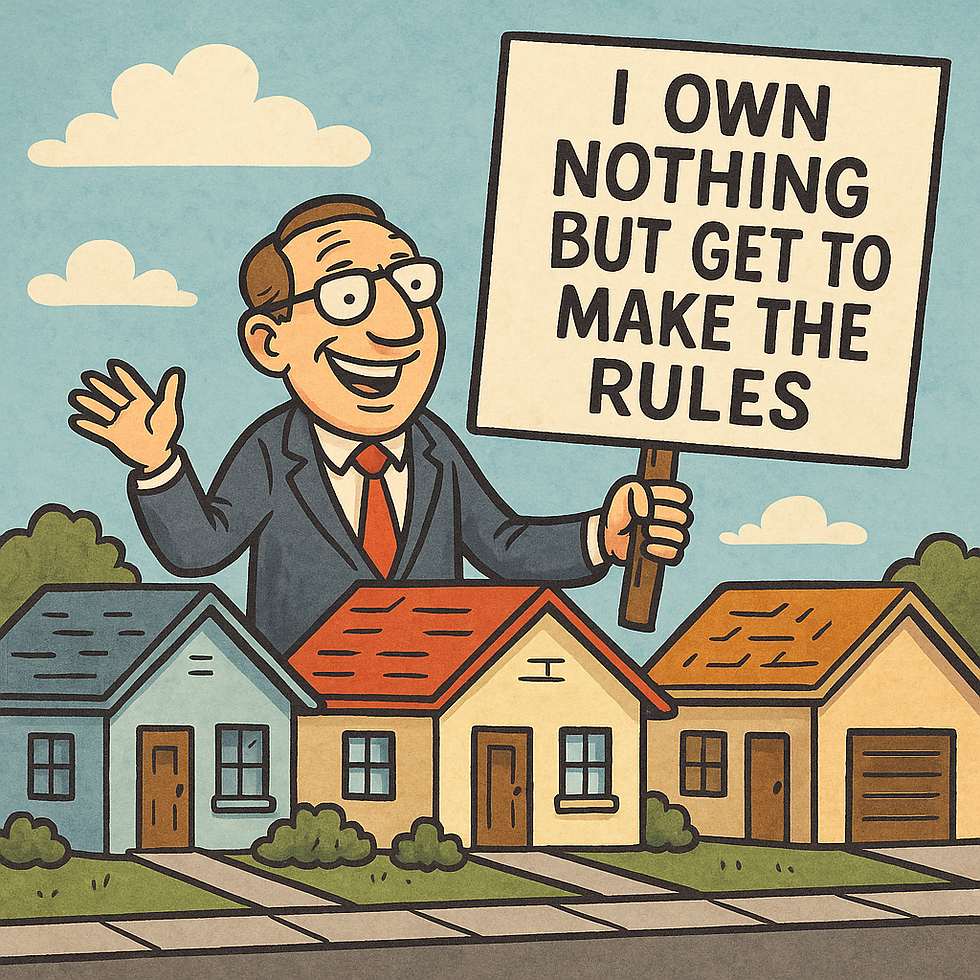

It is often said that “developers have a lot of voting rights because they still own a bulk of the community property.” That is not necessarily true. A declarant may not own any material amount of property in the association at all- and still exercise significant governance power.

The key word is “in” — meaning property formally annexed into the association (a developmental right discussed below).

In practice, developers often keep property they plan to annex outside the association until it is sold to a builder or final homeowner. By holding land (or “units”) in this way, they avoid paying assessments to the association — among other advantages.

A second common misconception is that a developer’s “control” comes from owning units in the association. In reality, control is a legal construct, not simply a matter of ownership. The law allows developers to reserve a package of contract rights in the declaration that gives them governance authority regardless of whether they own many units, few units, or even none at all.

And here is the most important point: while the community is under declarant control, the declarant and its appointed directors owe fiduciary duties to the owners, akin to those of a trustee.[1] Nevada law requires them to act in good faith and in the best interests of the association — not in the interests of the declarant. But are they, or even can they, be held to this standard?

When the Uniform Law Commission (ULC) first drafted the UCIOA which Nevada adopted as its HOA law, it emphasized that declarant-appointed directors should be held to trustee-level duties, because they were exercising control on behalf of owners during the development phase. Nevada’s lawmakers went even further. Instead of limiting trustee-like duties to declarant appointees- as the ULC suggested- Nevada flattened the rule and applied fiduciary obligations to all directors, whether appointed or elected.

In doing so, Nevada signaled that every board member must act with loyalty, care, and good faith toward the association and its members — akin to those of a trustee- not as an agent of the developer or others.[2]

But does this carryover in practice?

Two “Rights,” Two Loopholes

Nevada law, like that of most states, gives developers special control tools to build large common-interest communities (CICs). These are called developmental rights (DR) and special declarant rights (SDR).

In principle, they make sense: developers need the flexibility to add phases, finish amenities, and keep the project moving until enough homes are sold. But what was meant as a temporary bridge can become a permanent lever.

Nevada treats declarations as if they were ordinary contracts. But they are not. HOA’s are quasi-governmental entities. Developers write the contracts (HOA “constitutions”), Nevada regulators do not review them, and the result is CC&Rs that can preserve developer authority long after construction is complete and long after homeowners believe they should be in charge.

The two biggest loopholes:

Indefinite Governance — developers retain veto and approval rights even after owners elect the board.

Indefinite Declarant Control — developers manipulate turnover thresholds so their appointees keep the board majority.

Both DR and SDR authorities have been around for decades — since Nevada first adopted the UCIOA in 1991. They are essential to making HOAs work — but they can be abused. The abuse potential is well known to the professionals and lawyers who serve developers — but rarely disclosed clearly to homebuyers. Together, they can leave owner elections potentially symbolic.

The Duty of Good Faith

Nevada law (NRS 116.1113) imposes a statutory "obligation of good faith" on declarants. The statute states:

“Every contract or duty governed by this chapter imposes an obligation of good faith in its performance or enforcement.”

And under Nevada’s Uniform Commercial Code (NRS 104.1201), “good faith” means “honesty in fact and the observance of reasonable commercial standards of fair dealing.”

Taken together, these provisions create a clear expectation that declarants act with honesty, loyalty, and fair dealing.

As you read what follows, ask yourself: when declarants insert provisions like these into the CC&Rs — the constitution of the community — are they acting in good faith? My opinion is no.

Hole #1: The “Declarant Rights Period”

One of the most damaging flaws in Nevada’s HOA framework permits declarations to create a concept not defined in the statute at all — a “Declarant Rights Period.”

The term, which may appear under different names, is meant to capture various rights in favor of the developer (usually termed the “Declarant”). It typically reads something like this:

“Declarant Rights Period: The period of time during which Declarant owns any property subject to this Declaration or which may become subject to this Declaration by annexation … during which period Declarant has reserved certain rights as set forth in this Declaration.”

What These Rights Look Like

Here are some examples of rights commonly tied to such a clause:

Rules and Regulations: No amendment effective without declarant consent.

Architectural Guidelines: Declarant retained unilateral authority to amend standards.

Neighborhood Boundaries: Declarant could redesignate boundaries.

Neighborhood Common Elements: Any assignment or reassignment required declarant approval.

Common Facilities: Facilities had to remain in continuous operation unless declarant agreed otherwise.

Services and Use: The board could not change services or repurpose areas without declarant consent.

What It Means

Even if the developer no longer has a seat on the board, these clauses give it control over most of the material levers of governance.

Powers the developer held during declarant control can remain in its hands after turnover — not because the developer is still materially building or selling, but because of a statutory hole that allows declarations to define a “Declarant Rights Period” on terms that can extend power indefinitely.

A single annexed parcel is enough. In a 10,000-home development, if the developer keeps just one unit- even if that unit is his for example, his own home- the Declarant Rights Period stays alive — and with it, sweeping approval powers.

Any un-annexed parcel listed in the CC&RS is enough. As long as it lists land that “may become subject,” the Declarant Rights Period stays open.

Ownership isn’t required. CC&Rs can list land the developer never owned — for example, Federal Bureau of Land Management (BLM) land it merely hoped to acquire someday. The paper listing is enough to extend declarant rights.

This is how a law intended to bring about owner control ends up producing only the façade of owner governance. And the most troubling part: after decades, this loophole remains wide open.

Hole #2: “Maximum Number of Units”

Nevada’s control turnover statute (NRS 116.31032) requires owner-elected directors to phase in as homes are sold, and full turnover of the board once a percentage of the total “units” are conveyed:

For most associations, the threshold is 75%.

For larger associations (over 1,000 units), the threshold was 75% until 2015. With AB 192 (2015), lawmakers inexplicably raised it to 90%.

This means a developer can hold as little as 10% of the maximum units — in a 10,000-unit community, just 1,000 — and still appoint the majority of directors.

The Problems Multiply

No annexed units required. The developer need not hold any annexed units — paying no assessments — and still appoint a majority of directors.

No ownership required. The developer need not own any units at all. So long as the CC&Rs list parcels that may be annexed someday, those “phantom” units keep control alive.

Inflated maximums. The developer sets the “maximum number” in the CC&Rs with no requirement to show it could actually build that number. By inflating the maximum, turnover is delayed or can be effectively denied altogether.

Why This Matters

Conflicted decision-making. Declarant-appointed directors may understandably, especially if employed but the declarant, answer to the developer’s interests, which will inevitably conflict at some point with those of owners.

No real accountability. Owner directors may sit at the table, but without a majority their voices can be overridden. And, since conflict of interest (COI) issues are addressed by the board, COIs when then occur are unlikely to surface. (Government entities and many private companies have independent ethics review.)

Delayed reform. Even when owners see problems, they may lack the votes to act until long after the project is built out.

The Needed Fix

Return Nevada to the 75% threshold. Recognize that developers have the necessary tools to complete projects without holding board majorities to unnecessary levels.

Bar employees or affiliates of the declarant from serving on the board while the declarant is exercising “control”. Consumer protection and lack of conflict-of-interest controls pose too high a risk given the complexity, proliferation, and adhesive nature of declarations. (The potential need for declarant support of the board in the very early stages of development can be addressed separately.)

Tie turnover to "doable" at the time. Base turnover on the number of units that can be demonstrated, not inflated maximums or speculative “may become” parcels or needs. How can owners expect fair representation from what is unknown or tied to the future.

Mandate clear disclosure. Require developers to state plainly when control will pass to owners — and on what assumptions.

All of these are considerations for change proposed by NVHOAReform and can be found here.

The Larger Lesson

Both the Declarant Rights Period and the inflated “maximum number of units” exploit drafting gaps in Nevada’s law. The real danger is not just these two loopholes, but in a system that allows developers to unilaterally write foundational contracts used by the general public with no regulatory oversight.

As long as Nevada treats CC&Rs as private bargains immune from public standards or meaningful oversight, declarants will continue to find new ways to tilt governance in their favor. Unless lawmakers draw a clearer line — limiting the reach of declarant rights and requiring meaningful review — homeowner governance will remain an illusion.

Elections may look like democracy, but without reform they will remain merely symbolic as will the idea of homeowner associations.

_______________________

[1] To our knowledge no Nevada appellate court has directly ruled that declarant-appointed directors stand in a trustee relationship with the association. But the statutory framework imposes fiduciary duties that are functionally equivalent. NRS 116.3103(1) requires all directors to act “on behalf of the association,” and NRS 116.31034(9) requires declarant appointees to “act in good faith and in a manner [they] reasonably believe to be in the best interests of the association.” Overlaying this is NRS 116.1113, which imposes a duty of good faith and fair dealing on every duty and contract under Chapter 116. Taken together, these provisions establish duties of honesty, loyalty, and care that mirror those of trustees.

The Uniform Law Commission, in its Official Comment to UCIOA § 3-103 (1982), explicitly noted that declarant-appointed directors should be held to “the standard of care applicable to trustees,” while owner-elected directors could be judged under the business judgment rule. Nevada, however, did not adopt this distinction: its 1991 enactment of NRS 116 imposes fiduciary obligations on all directors alike.

The Restatement (Third) of Property: Servitudes reinforces this approach. Section 6.13 establishes association duties to treat members fairly and act reasonably in discretionary powers, and § 6.14, comment b makes clear that “because the stakes are so high, directors and officers should be held to high standards of honesty and fair dealing” and that “analogies drawn from duties of loyalty imposed on corporate directors and private trustees may be appropriate. They should be applied with an eye to the special character of community associations” Restatement (Third) of Prop.: Servitudes §§ 6.13, 6.14 cmt. b (2000).

[2] In my view, the Uniform Law Commission got this part right. Declarant-appointed directors should be held to trustee-level duties because of their close relationship with the developer and the inherent conflict of interest that arises during the period of declarant control. Their role requires a heightened level of loyalty and impartiality, since they are positioned between the developer’s private interests and the community’s collective interests. I do not agree, however, that owner-elected directors should be held to the same trustee standard. These directors are chosen by and accountable to their neighbors, and while they must act in good faith and with due care, it is unrealistic — and, in practice, chilling — to expect unpaid volunteer owners to carry the same level of fiduciary burden as a trustee. Nevada’s flattening of the UCIOA framework, which imposes trustee-like duties on all directors alike, may have overcorrected by treating owner-elected volunteers as if they were professional fiduciaries rather than community representatives.

**We are not attorneys and any written or electronic communications is provided here or on this site as a service to the internet community. Any advice that is provided on this site is based on our experience. Consult an attorney for legal advice..

Comments